Happy New Year!

Birds Eye View Sound & Silents – Sumurun and The Adventures of Prince Achmed

Birds Eye View is one of Silent London’s favourite film festivals – a celebration of female film-makers with an exceptionally strong and musically adventurous silent cinema strand. Last year, even though the festival was on haitus, the Sound & Silents programme brought us a selection of newly scored Mary Pickford films. This year, in keeping with the overall theme of the festival, the screenings have an Arabian flavour.

The two films in the Sound & Silents segment are, to be frank, German – but the first, Lotte Reiniger’s trailblazing cutwork animation The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) is based on a story from 1,001 Arabian Nights, as also, perhaps more loosely, is the second, Ernst Lubitsch’s boisterous harem farce Sumurun (1920). Achmed, widely acknowledged as the first animated feature film, and still as elegantly beautiful today as in the 1920s, probably needs no introduction from me.

The latter film is a slightly guilty pleasure of mine – a rather well-made romp, enlivened by the sinuous presence of the young Pola Negri, and the more demure charms of Swedish ballerina Jenny Hasselqvist. Lubitsch himself appears as a leery clown with hunchback, but his real star turn is behind the camera, crafting a fast-paced and vivacious comedy out of unpromising material. Sumurun had been a stage hit for Max Reinhardt’s company in Berlin, and Negri had starred in both that production as well as one back in her hometown of Warsaw – perhaps it’s therefore no surprise that this film is so slick, with such larger-than-life performances, including Paul Wegener as a bully-boy sheik. I will concede, of course, that it is rarely, if ever, politically correct.

Sound & Silents is as much admired for its musical commissions as its programming, and it’s intriguing that these German Arabian pastiches will be accompanied by scored from musicians whose roots lie in both Western Europe and the Middle East – British-Lebanese Bushra El-Turk and Sudanese-Italian Amira Kheir.

Multi-award-winning contemporary classical composer Bushra El-Turk creates a new work for a chamber ensemblecombining classical Western and traditional Middle Eastern instrumentation, accompanying The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the world’s first feature-length animation. Currently on attachment to the London Symphony Orchestra’s Panufnik Programme, British-Lebanese El-Turk’s acclaimed work has also been performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and London Sinfonietta.

Singer, musician and songwriter Amira Kheir blends contemporary jazz with East African music for a multi-instrumental 5-piece band, scoring landmark fantasy-drama Sumurun (One Arabian Night). Kheir has recently won acclaim for her ‘beautiful and fearless’ (Songlines) first album and her BBC Radio 3 and London Jazz Festival debuts.

Initially at least, the Sound & Silents screenings will be held in London and Bristol. Bushra El-Turk’s score for The Adventures of Prince Achmed premieres at a screening at the Southbank Centre on Thursday 7 March, with a second performance on Friday 5 April at the Barbican. Sumurun plays with Amira Kheir’s new score at BFI Southbank on Thursday 4 April and will then show at the Watershed Cinema in Bristol on Sunday 14 April. Click on the links for more information and to book tickets. Find out more about Birds Eye View here.

Sumurun: Ernst Lubitsch and Pola Negri’s Arabian night

This is a guest post for Silent London by Kelly Robinson.

Sumurun screens with a live score by Amira Kheir at BFI Southbank as part of Birds Eye View Film Festival on Thursday 4 April at 6.10pm. Read more here.

Sumurun is the product of an intensely creative time in the German film industry when an extraordinary range of artistic and entrepreneurial talent emerged: creating ambitious films that challenged American productions for the international market.

Paul Davidson, the director of the German production firm Projektions-AG Union (PAGU), was a film producer unafraid of financial risk-taking and he invested large amounts of capital early on in the industry. In 1918 the company was merged with several other firms under the umbrella of Ufa, with Davidson becoming an executive on its board. Much of Ufa’s success was the result of the absorption of PAGU’s talent, which included directors such as Ernst Lubitsch and Paul Wegener and stars such as Pola Negri and Ossi Oswalda. Indeed because of its established reputation it still produced under the PAGU brand and retained a considerable degree of independence.

With financial support from the German bank, Ufa began a policy of big-budget films aimed at the international market. In 1918, Davidson suggested Lubitsch try making one of these Großfilmes, epic productions indebted to the Italian spectacle films, such as Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914) – films which in their budgets and enormous sets were an attempt to compete with Hollywood. Lubitsch assembled a regular production team around him for a series of these ambitious films, including his co-writer Hanns Kräly, the set designer Kurt Richter, and cameraman Theodor Sparkuhl. Famous actors such as Pola Negri added star allure to these films and became a big draw for audiences’ world-wide. Sumurun is one of several extraordinary films that resulted from these collaborations during the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Pola Negri was born Barbara Appollonia Chalupiec in Yanowa, near Lipno in Poland. She took as her professional name the last name of Ada Negri, an Italian poet she admired and the diminutive form of Apollonia as a first name. She had danced at the Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg and had acted on stage and screen in Poland before being invited by Max Reinhardt to Germany to star in Sumurun (a story derived from The Arabian Nights) after she had appeared in a Polish theatrical version. It was here that Negri met Lubitsch, who was a Reinhardt player and comedy short director at the time, and who was playing the role of the hunchback opposite her in the German theatrical version (a role he would recreate in the film). They became good friends and he made her the star of several of the large-scale costume pictures for Ufa. Lubitsch told her: “We’re going to make a picture of Sumurun. Reinhardt’s letting us have the sets and costumes. We’ll use most of the actors from the stage productions. We’ll hardly even have to rehearse. It’ll cost practically nothing.” (Pola Negri, Memoirs of a Star). Production started in September 1920. It was substantially cut and released by First International in the US in October 1921 with the new title One Arabian Night. Negri remembered its production as: “a very easy and happy chore. Except for a few Lubitsch innovations, it was essentially a photographed stage play.” (Memoirs of a Star)

This kind of dismissive assessment has plagued One Arabian Night, with even relatively recent biographies of Lubitsch granting the film scant attention. However it is an important film, both as an example of Germany’s aesthetic advancements and also in the context of Negri’s and Lubitsch’s career. For instance it was this film that impressed Mary Pickford so much that she brought Lubitsch to the US for Rosita (1923). The film’s critical neglect is most likely a result of viewing the bowdlerised US print, which is missing thirty minutes. Thankfully now we can see the fully restored version.

Many historians agree that German films improved when Hollywood films began to be seen in Germany from 1921, and yet, interesting approaches to cinematography preceding the American influence are evident in films such Sumurun. For instance, in the opening of the film where the light streaming through blinds in the caravan causes chiaroscuro patterns. Cameraman Sparkuhl also has a tendency to hold closeups from a high angle, which adds variety to some of the scenes. Indeed, most of the closeups of Pola Negri, particularly the scenes of her dancing in Sumurun, are shot in this manner. This may have been a way of singling Negri out from the rest of the characters; similar to the technique of filming stars that was developing in Hollywood.

German film’s reputation for elaborate set design is evident in Sumurun. There is a rhythm both in the set design and also in the movement of figures within that design. Lotte Eisner has noted how the American musical would pattern itself on the “delicate arabesques” in this film (The Haunted Screen). Contemporary reviews often observed how Lubitsch’s films were on a par with the best American productions. Variety reviewing the film in 1921 commented: “The production is colorful throughout, the atmosphere of the East being perfect in detail.” These films were incredibly successful in Germany and abroad. Their settings, such as Sumurun’s Persia, and subject matter, offered audiences an escape from everyday reality. Negri observed that “one of the reasons [for the success of Sumurun] was certainly because its intensely romantic oriental fatalism was precisely the kind of escapism a war-weary people craved for” (Memoirs of a Star).

Negri and Lubitsch were among the first international celebrities to be brought to the US – later director-star duos included Mauritz Stiller and Greta Garbo. Negri arrived under contract with Paramount in 1922 to a storm of publicity. The press went wild over an affair with Charles Chaplin and supposed spats between her and Gloria Swanson, whose top star status at Paramount she challenged. Her vampish screen persona was conflated with anecdotes about her private life. The press spread rumours about her many lovers and delighted in reporting quirky acts such as her walking a tiger on a leash down Hollywood Boulevard.

Negri had became known abroad for playing roles where women exploited their sexuality for economic and political gain (see also Carmen and Madame Dubarry). Her swaggering sexuality is parodied sublimely by Marion Davies in The Patsy (1926). Diane Negra has observed the transformation that her persona undertook in the move from Germany to Hollywood. In the Hollywood films her femme fatale image was tempered and the films frequently ended happily. The American films also deemphasised the ethnic and class dimensions found in earlier films. Her US films were not as successful as the European ones and Negra argues that this was the result of her ethnic sexuality. Her Italian surname, Polish ethnicity and connections to German film industry meant she could not (or would not) be fully assimilated. In public and private she appeared to resist being Americanised. “As the unassimilatable woman, both in ethnic and sexual terms, she stood for a type that was in fact far more transgressive than the thoroughly American, upper-middle-class flapper who, for all her supposed flouting of social conventions, was nearly always safely married off in the end.” (‘Immigrant Stardom in Imperial America: Pola Negri and the Problem of Typology’, Diane Negra).

Kelly Robinson

The top 10 silent film dream sequences

This is a guest post for Silent London by Paul Joyce, who blogs about silent and classic cinema at Ithankyouarthur.blogspot.co.uk. The Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts.

Cinematic dreams are a staple of the silent era more than any other, possibly because much of what was on screen had only previously been experienced in dreams for contemporary audiences. Now our dreams are founded on over a century of cinema and we’re so much harder to impress but … we can still dream on. Here’s a top ten of silent dreams with a couple of runners up as a bonus.

The Astronomer’s Dream (1898)

A madly inventive three minutes from George Méliès in which an old astronomer is bothered by a hungry moon as the object of his observation makes a rude appearance in order to eat his telescope.

Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906)

A feast of special effects in Edwin S Porter’s cautionary tale on the matter of over-indulging in beer and cheese. Jack Brawn plays the titular fiend who suffers all manner of indignities once he staggers home to his bed, whereupon his sleep is interrupted by rarebit imps and his bed flies him high into the night sky … Proof that the whole cheese-and-dreams rumour is actually true.

Atlantis (1913)

In August Blom’s classic – the first Danish feature film – Olaf Fønss’ doctor dreams of walking through the sunken city of Atlantis with his dead friend, as the passenger ship he is on begins to sink. It’s either a premonition or recognition that his true feelings have been submerged … JG Ballard was obviously later inspired to write The Drowned World.

Poor Little Rich Girl (1917)

After being accidentally overdosed with sleeping draught by careless servants, Mary Pickford’s character falls into a deep and dangerous sleep … As she hovers on the edge of oblivion the story runs parallel between the doctor trying to save her and her dreams in which those she knows are transformed in her Oz-like reverie. Sirector Maurice Tourneur excels as “the hopes of dreamland lure the little soul from the Shadows of Death to the Joys of Life”.

When the Clouds Roll By (1919)

Douglas Fairbanks is harassed by vengeful vegetables after being force-fed too many in an effort to drive him to suicide (yep, it’s a comedy). Directed by Victor Fleming, who later returned to dreams with Dorothy and that Wizard.

The Wildcat (1921)

Pola Negri dream-dances to a snowmen band in Ernst Lubitsch’s absurdist romp. Then she eats her lover’s heart as a biscuit. But of course … Negri flings herself around the bed and blows out her cheeks as she dreams, barely stifling a mile-wide smirk. Lubitsch’s comedy overdrive is Pola-powered!

The Haunted Castle (1921)

Murnau’s narrative here is more concerned with haunting guilt than spirits, yet one especially nervous house guest dreams of sinister, spindly arms reaching in to drag him away from his room in the night. It’s vaguely familiar, but Count Orlok was merely biding his time and he would oversee a proper haunting in the following year’s Nosferatu.

Sherlock Jr (1924)

Buster Keaton’s projectionist falls asleep and dreams of solving the crime he is accused of committing, famously walking into the film he is projecting to do so as people from his real life start appearing as characters on screen. After a breathless sequence of comedic capers, he wakes to find that his girl has sorted everything out for him! Good things happen to those who dream.

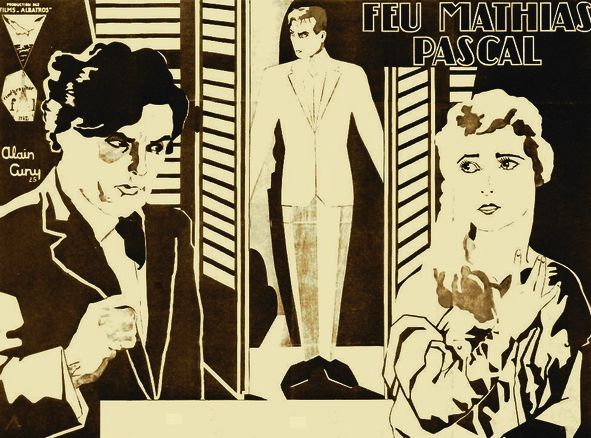

Feu Mathias Pascal (1925)

Ivan Mosjoukine’s Pascal has visions of battling himself as he tries to reconcile his assumed identity with his original one, then he daydreams a vicious attack on his lover’s fiancé. Superb technical work from director L’Herbier illustrating his character’s conflict: the film’s reality is scarcely different from the dream.

A Page of Madness (1926)

An old man dreams of saving his mad wife’s life in Teinosuke Kinugasa’s brilliantly disturbing examination of the nature of sanity … or does he? Masuo Inoue gives a quite brilliant performance, providing us with an identifiable “hero” whose shifts into hysteria are all the more shocking for that. But does he actually lose it or does he dream it?

Runners up:

The Devil’s Needle (1915)

Tortured artist Tully Marshall dreams of seeing fairies in his fireplace. Drugs are involved and it’s all Norma Talmadge’s fault!

Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924)

Yakov Protazanov’s sci-fi parable turns out to be all a dream, but I wanted the costumes to be real!

By Paul Joyce

Do you agree with Paul’s choices? Share your suggestions below

Lubitsch in Berlin: box set review

We’re an excitable bunch here at Silent London, which you have probably noticed by now. But a quiet announcement by Masters of Cinema recently caused even more whooping and merriment than usual. The classic movie imprint is releasing its gorgeous Lubitsch in Berlin box set, which had inexplicably fallen out of print. We’re big fans, big, big fans of this set, and so in a collective declaration of box set love, a group of us gathered together to review every movie in the box, one by one …

There are six films in the set, all made by the legendary Ernst Lubitsch in the earliest stages of his movie career, after he had been lured out of Max Reinhardt’s theatre company to the UFA studio. If these films are deemed less sophisticated than his later Hollywood work, then that is mostly because his subject matter is often more fanciful, his characters border on feral, and his sense of humour, at this time, in uninhibitedly mischievous. Or perhaps, because people are fools. The elusive “Lubitsch touch”, and his mastery of character, space and comedy is very much in evidence here – The Oyster Princess and Die Puppe in particular are perfectly pitched comic pantomimes. Three films in this box star the irrepressible German comic actress Ossi Oswalda – perpare to fall head over heels – a further two feature the wonderful Pola Negri and Emil Jannings makes an appearance too.

One of the films in this set, Anna Boleyn, was partially responsible for Lubitsch’s move west: it and Madame Du Barry (not in this set) found US distribution, and became unsettlingly successful on those shores. Lubitsch would bc the first established Hollywood talent to be snapped up by a Hollywood studio. Pola Negri would follow shortly after – they called it, sardonically, the “German Invasion”.

As well as the following six films, the set contains a feature-length documentary (Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin: From Schönhauser Allee to Hollywood) and some very sharply written essays. Don’t miss out.

I Don’t Want to be a Man (1918)

Reviewed by Pamela Hutchinson

The exclamatory title of this 40-minute caper is a lesson hard won for its capricious heroine. One might add, she hardly wants to be a woman either – at least not her fretful elders’ idea of how a young woman in her teens, and the century’s, should be. Delightfully, other people’s ideas hardly get a look in. I Don’t Want to be a Man is a taboo-thumping caper that plots its own course through conventional ideas about gender and romance. It was early days for Weimar Berlin when this film was made, but even in this short comedy, there is lechery, bisexuality, drunkenness and decadance in abundance. And when it comes to rebellious on-screen teens, Ossi Oswalda’s flirtatious, gender-bending minx feels decidedly modern.

Ossi is a smirking teenage nightmare, a spoilt brat who smokes and plays poker with men much older than her. Banished to her room, the flirting continues through her window as her suitors contort themselves on the pavement below. When he is called away overseas, her uncle hires a new, supposedly strict, young guardian to take her firmly in hand. That the appointed dragon is a handsome young man may seem to spell trouble. But Ossi’s next move takes the story to a whole new level of larkiness.

Outraged at being grounded, Ossi decides the only possible way to enjoy a night on the tiles is in drag, so she has herself fitted for top-hat-and-tails and sneaks out of the house. I won’t give away what happens in the nightclub, and the morning after, but suffice to say that lust and confusion bloom in equal measure.

A running gag here is that as a woman, Ossi can handle herself and manipulate the men who throng her, expertly. As a man she is clueless and not a little afraid. At the tailor’s in, feminine dress, she parcels her body out to the adoring assistants who clamour to measure her up: a left arm for one, the waist for another. In the club, she is near toppled over by the women who want to dance with her. Whether Lubitsch is saying that when it comes to sex women have the upper hand, or just poking fun at the whole business of romantic chivalry matters little. That Ossi finds herself a partner who likes her both in drag, and out of it, is the happy ending that even the most “retrosexual” audience could crave.

(If you enjoy this film, I implore you to seek out Karin Swanstrøm’s Flickan i Frack too.)

Die Puppe (1919)

Reviewed by Alex Barrett

If it’s well-known that silent cinema is littered with heavily stylised classics, it’s perhaps also true that Die Puppe remains one of its most overlooked gems – a pre-Caligari classic of German artifice. Used here for comedic (rather than psychological) ends, the stylisation is no doubt employed in part to help make believable the film’s central premise: when a wealthy baron decides his nephew must marry, the local monks talk the nephew into marrying a lifelike doll so he can donate his dowry to their abbey. But what the nephew fails to realise is that the dollmaker’s puckish apprentice has broken the doll, and that his bride-to-be is in fact the dollmaker’s daughter herself, and not her mechanical counterpart …

If that all sounds rather silly … well, it is. But the nephew’s response to his uncle questioning the doll’s (literal) stiffness (“She’s from an old patrician family. They’re all very formal”) reminds us that this is as much social commentary as social comedy. The film is at its most pointed when representing the hypocrisy and greed of the monks, who gorge themselves on food and wine while claiming poverty (their response to the news of the 300,000 francs dowry: “Do you know how many pork knuckles you could eat for that!”).

The film was a vehicle for then-popular German actress Ossi Oswalda, who excels here in the dual role of the doll and the dollmaker’s daughter. But the film itself undoubtedly belongs to Lubitsch; he appears first onscreen, unpacking what is to become the scenery of the film’s opening scene. The film is subtitled “Four amusing acts from a toy chest”, and if the four acts never quite emerge in the print presented here, the rest of that description seems particularly accurate. Moving beyond stylisation-for-the-sake-of-it, Lubitsch seems to be delighting in the very medium of cinema and the possibilities inherent in the art form (lest the film’s exuberance make us forget, Die Puppe was made in 1919). Lubitsch is director as conjurer, and the film’s reflexive and playful edge exhibits all the purest joys of the silent era – a time in which cinematic conventions were yet to come along and ruin the experimental, stylised fun.

Alex Barrett is an independent filmmaker and critic. He is currently in development with his new film, London Symphony, a silent city symphony. You can follow the project’s progress on Facebook and Twitter.

Die Austernprinzessin (1919)

Reviewed by Ewan Munro

One of the wonderful things about silent cinema is that film techniques and technologies we nowadays take for granted were still evolving. This occasionally means we get stagy affairs with huge melodramatic emotions matched to over-the-top gestural acting and a sense of decorum a hundred years removed from our own sensibilities. Yet for every ten of those there’s a film like Die Austernprinzessin: constantly inventive, filled with laughs, and with a satirical sense that doesn’t feel hugely out of step with anything being made today. The director is Ernst Lubitsch, who at this point was still making his name. He even had a brand of sorts, the “Lubitsch touch”. Whatever that may be, he certainly does have a way with a film, no less in this early effort than in many of his “mature” works.

At the heart of The Oyster Princess is a pretty full-blooded critique of capitalism; there’s certainly no pulling punches here. The “oyster king”, Mr Quaker (Victor Janson), lives in a vast mansion attended by numerous servants and has a spoilt daughter, Ossi (Ossi Oswalda). Until the very end, all that either seems to care about is this privileged life they live. Quaker’s catchphrase, delivered at the end of each of the movie’s four acts, is “that doesn’t impress me”. Ossi, meanwhile, who kicks off the plot with her demand to marry a prince, susbequently pays only scant attention to either the man or the relationship. Hers is an entitled world of passing whims, and she soon decides that this prince she’s been given isn’t one she likes very much after all.

But this is a comedy of manners, and part of the joke is that Prince Nucki (Harry Liedtke) has fallen on hard times, and so has sent his valet Josef (Julius Falkenstein) to check out Mr Quaker’s offer. This somewhat inevitably leads to him being confused with the prince, and given the frivolous way the Quakers live, perhaps that’s little surprise. The opening shot shows Mr Quaker smoking an unreasonably large cigar, attended by a phalanx of obsequious black servants, while his every word is hung upon by an array of secretaries. This obscene overkill – Quaker doesn’t need so many women to transcribe his dictation, nor so many handservants, as most of them have nothing to do – quickly becomes a running joke. There are serried ranks of servants to help Ossi into and out of her bath, and serving a meal is like a military drill. This is obscenely gluttonous excess for its own sake – and for our amusement.

Although the technical limitations of the period mean the camera is still largely fixed, it’s hardly noticeable thanks to a lightness of touch in orchestrating the action. Characters move around incessantly. So vast is Quaker’s mansion that he, attended by his many servants, jogs from room to room. His daughter meanwhile is a whirligig of emotion, throwing everything around petulantly. At one point there’s even a dance sequence – “a foxtrot epidemic breaks out!” – allowing for various groupings around the mansion until eventually everyone, right down to the kitchen servants, is seen dancing.

It may not be surprising to devotees of Lubitsch’s work, but for one new to his cinema, what’s astonishing is that almost every moment in the film’s concise hour-long running time is filled with inventiveness and comic inspiration. Shots that just prosaically bridge a gap between two scenes are not for Lubitsch, and (as mentioned above) even moving between rooms is done with a humorous touch. The performances are also uniformly delightful, particularly Oswalda’s cheeky impishness and Janson’s amusingly affected stoicism.

Once again, this is another excellent Masters of Cinema release, with an exemplary transfer to DVD and a rather jaunty score perfectly matched to the action on screen. This isn’t just an excellent primer to Lubitsch’s cinema, or to silent screen comedy. It’s a marvel of a film and a joy to watch.

You can read more of Ewan Munro’s reviews at filmcentric.wordpress.com

Sumurun (1920)

Reviewed by Peter Baran

Of the silent genres which seem to have dissipated when sound came, the Sheikh & Sex desert romances can seem the most alien to us now. Not just for their broadly orientalist strokes, any silent film aficionado has to swallow to some degree the racial and jingoistic views of the time, but there is often a degree of exotic ethnography going on, from Valentino’s tea-towel headgear to the huge harems on display. In depicting a non-Christian world view, film companies could have their cake and eat it, tell highly sexualised stories without condoning them.

Sumurun, with all of its high melodrama, probably sits closer to Lubitsch’s sex comedies such as The Oyster Princess, but its source material and setting means that narratively at least there is a sense that the story is the most important thing. Whilst the film is invested in the capricious evil of its sheikh, and definitely leaning on the fetishisation of the harem and exotic dancing, Lubitsch does not seem to be moralising here. Instead he is using his setting as an alien world, building a blockbuster that throws all the spectacle it can muster on to the screen whilst trying to display humanity in all its characters.

This means that tonally, Sumurun is a bit of a mess. It lurches from slapstick to scenes of murder and ends with some high tragedy. This doesn’t really matter though, as the narrative thread is strong and like any blockbuster there is barely a moment where Lubitsch doesn’t put something funny, novel or just plain beautiful at the screen. Pola Negri is appropriately captivating as the travelling dancer who instigates the ruckus, but Jenny Hasselqvist’s Sumurun is suitably empathic in the title role as the seemingly doomed courtesan. The film, however, belongs to Lubitsch the actor, whose Hunchback both observes and drives the story but also holds the most significant emotional beats (and some of the broadest comedy). He does a lot of eyebrow acting, and is extremely watchable in the role. That said, by the time people are locked in trunks, and are being chased around the elaborate set like a Hanna-Barbera cartoon, the hand of Lubitsch the director is clearly more prominent.

Much like its source material, Sumurun is invested in entertaining a wide audience in the broadest way. It has a Shakespearean sweep in its tragedy, but is at its heart a comedy – and quite a silly one in places. That it works is due to Lubitsch taking rather broad archetypes, particularly his own, and breathing life into them, transforming them from comedy to tragedy. It feels apt that the last shot of the film is Lubitsch himself, in his final acting role, mournfully strumming a lute; he will go on to entertain behind the camera, but he gives himself a pretty meaty final role.

Anna Boleyn (1920)

Reviewed by Kerry Lambeth

For the star of a story about a sexy tempter lady, Anne Boleyn (Henny Porten) doesn’t get to do a lot of tempting. The queens on either side of her have much more fun: her predecessor Catherine of Aragon (Hedwig Pauly-Winterstein) gets some spectacular eye rolls and glares in, and successor Jane Seymour (Aud Egede-Nissen) interestingly takes up the traditional “Anne Boleyn” role of the ambitious, flirtatious younger woman who lures away Henry VIII (Emil Jannings). Porten’s Anne is very Good and Virtuous and Tragic. Far from scheming to get Henry and the crown, she is pressured into the marriage by the king and her uncle Norfolk (Ludwig Hartau). The best shot of the film is of the two men exchanging glances over her head, then talking rapidly at her from both sides as she slips into a half-swoon between them.

The three leads are introduced with very successful contrasts: Anne’s energy as she runs across a courtyard to greet her fiancé Henry Norris (Paul Hartmann); Henry’s joie de vivre as he licks his fingers and drinks from a tankard bigger than his head; and Catherine’s ritual, stultified staging of monarchy in the court.

Lubitsch frames Anne in playful boxes throughout the film. The opening scene sees her in a rocking cabin on the sea from France, she kisses Norris over a half-door and meets Henry VIII when the train of her dress is caught in a door. The set traps her but the camera dangles the possibility of escape. After she is sentenced to death, she begins to stride toward the camera, nearly faces us head-on, but chickens out and ducks away down a side corridor.

As a little bonus, the new score has a few jokes for early modern music fans, as “Pastimes with good company” – a tune Henry VIII wrote himself – is heard at key moments: at the king’s introduction, sitting at a Round Table (do you see) with his knights, at a May fair and later in a minor key as things start to go wrong for Anne.

I suspect it’s a bit long and worthy for those who know Lubitsch for his comedies, but as a historical costume drama Anna Boleyn is a lot quicker and wittier than most contemporaneous films of that genre, and frankly most modern ones too.

Kerry Lambeth blogs about Shakespeare, history, travel and drinking at Planes, Trains and Plantagenets

Die Bergkatze (1921)

Reviewed by Philip Concannon

Ernst Lubitsch has referred to Die Bergkatze as his own personal favourite, and it’s easy to see why. This picture – which proudly proclaims itself as “A grotesque in four acts” – marks the peak of his silent era creativity. The film’s production design recalls The Cabinet of Dr Caligari with its spiral staircases and unusual angles, but filtered through the fantastic storybook style of Lubitsch’s Die Puppe, which he pushes to extremes here. We see the story unfold through a series of bizarre irises, from conventional circles to oblongs and squiggly outlines. Sometimes scenes are framed by an iris that suggests we’re viewing the action through a hole torn hastily in a sheet. It’s a suitably wild approach for the raucous tale Lubitsch wants to tell.

Die Bergkatze is the story of a soldier (Paul Heidemann) who finds himself caught between two women, one a captain’s eligible daughter (Edith Meller) and the other a gypsy girl – the “wildcat” of the title – who lives in the mountains with a gang of bandits. Her name is Rischka and she is played by Pola Negri, whose performance here almost matches the unrestrained exuberance of Ossi Oswalda in her collaborations with Lubitsch. Negri is lively and tough, manhandling and whipping the men around her into submission and stealing the leading man’s trousers within minutes of meeting him. While she takes steps towards a more feminine demeanour throughout the film, memorably trying on dresses and dousing herself in perfume, her more abrasive edges are never smoothed away – I loved the way she slapped away a proffered champagne glass before swigging straight from the bottle.

Lubitsch keeps undercutting convention in this manner. When we first see a crowd form to see off Heidemann’s Lieutenant Alexis, we might assume that it consists of people awed by his heroism in battle, but then we see that the throng is populated entirely by tearful women who want to thank “Alexis the Seducer” for the good times. Die Bergkatze is a gleefully entertaining romantic farce, with all of the wit and sauciness that characterises Lubitsch’s most distinctive comedies, but he also finds room for some unexpectedly touching interludes. A dream sequence that sees Rischka’s ghostly presence cavorting with Alexis is one of the loveliest scenes the director ever filmed.

Philip Concannon reviews films at Philonfilm.net

You can order the Lubitsch in Berlin box set from Movie Mail here.

Ten lost silent films

This is a guest post for Silent London by David Cairns, a film-maker and lecturer based in Edinburgh who writes the fantastic Shadowplay blog. The Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts.

More Silents by numbers posts

Madame Dubarry: Blu-ray and DVD review

Pola Negri’s Madame Dubarry has it. You know exactly what I am talking about. Dubarry is living and loving in the heat of pre-revolutionary Paris, but she’s more than enough trouble for the aristos all by herself. “The woman who will ruin France” is first introduced as a breath of fresh air, whispering saucy jokes to the other girls in the seamstresses’ workroom – a ripple of fun in the stuffy atmosphere of the atelier. When she leaves the shop, Dubarry collects admirers with every step, like Clara Bow in a crinoline. Before long, of course, she’s the mistress of Louis XV, creating disarray in the court, just as she did in the shop.

Ernst Lubitsch is brilliant at capturing this, the sizzle of sex appeal so hot that it can turn a king’s head, transform a society ball into an orgy, or raise an angry mob at the palace gates. Madame Dubarry has the angst of a drama, but the vigour of a comedy, and Negri has exactly the attitude that the part demands. Dubarry isn’t a calculating seductress, just a natural-born pleasure-seeker: a minx who decides which lover to visit by pouting as she pulls at the bows on her bodice. And Negri commits fully to the role of a beautiful woman in ugly circumstances – those enormous eyes are flirting one moment and filled with anguish the next. Some people are allergic to Negri’s grand emoting, the head flung back, the flailing arms. But there’s plenty there’s naturalistic and light here: watch her face as Jannings trims her fingernails, revelling in pleasure and pain. And yes, there’s also an opportunity for Negri to rehearse her most notorious scene – hysterically throwing herself across her lover’s coffin.

This Ufa production was an important film for Lubitsch and Negri both; retitled Passion to sound less alarmingly foreign, Dubarry was released in the US and captivated the critics (Mordaunt Hall acclaimed it: “one of the pre-eminent pictures of the day”). So much so that Hollywood beckoned for both director and star within a year. Negri’s co-star, Emil Jannings, who plays the dim-but-determined king, followed them soon after. Madame Dubarry may not be the best-remembered work of the Lubitsch-Negri-Jannings trio but the more I watch it, the further it seeps under my skin. These three have real chemistry.

Lubitsch once said that he gave up on acting himself when he saw Negri and Jannings perform together. Arguably his direction was part of what made them gel, but for a chance to see Lubitsch act, this dual-format release contains an archive gem. Als Ich Tot War, from 1916, is Lubitsch’s earliest surviving work, in which a henpecked hubby fakes his own death (in spite at his mother-in-law, of course) and then sneaks back into the household as a butler. It’s ragged, and a little static, but wickedly jovial. Lubitsch plays against his own preference, as a rather straight middle-class nobody rather than the broad Jewish “types” he commonly portrayed. It’s a wisp of thing compared with Dubarry, but worth it for a bizarre potato-peeling scene alone. Lubitsch was a great director, but a middling actor, and on this evidence, a rotten sous-chef.

But back to the main event – this film is not all about its star turns. Lubitsch’s crowd scenes are always a marvel, and the ones in Madame Dubarry are especially strong. Whether he is filling the frame with bewigged courtiers or raging peasants, Lubitsch understands the power that a mass of people can command: his crowds have character, and they bring the film to life. The revolutionary who pauses to slash a painting amid a palace raid, the jostling Parisians eager to gawp at the King’s envoy, the execution scene glimpsed through a jail-window grille. If Dubarry were a chamber romance, it would be striking, but the story Lubitsch is telling is bigger than that: of how the actions of lusty kings and greedy girls have far-reaching consequences. “All this because of a mistress!” So no matter how sumptuous the sets and how beautiful the gowns, it’s the drama that catches our eye. The sequence in which Madame Dubarry is presented at court, for example, is simply immaculate. As David Cairns writes in an insightful essay that accompanies this disc:

“[Lubitsch] succeeded most perfectly in humanising the denizens of the past, showing that the foibles that make modern man so ridiculous were just as evident in bygone ages. Though not a comedy, the movie uses comic declension to take the mickey out of kings and politicians and the great movements of history, showing the kind of bickering which lies behind them.”

Lubitsch’s film has the glamour and sweep of a historical drama as well as the intimacy of a romcom. The sets and costumes are gorgeous, the very best that Ufa’s ample resources could provide. The Blu-ray transfer here is crisp and brightly tinted – streets ahead of other versions I have seen – so while there are some marks of wear-and-tear, the image is clear and detailed. Presented this way, Madame Dubarry is a film to wallow in on a rainy afternoon: a concoction of sex and violence, politics and tragedy. It repays multiple viewings, and that’s why I’m a little disappointed that there is no audio commentary on this disc and fewer extras than we’ve come to expect from Masters of Cinema packages. It’s a small gripe however – this is a disc to treasure.

Madame Dubarry is released by Masters of Cinema on dual-format DVD and Blu-ray on 22 September 2014, priced £14.99. Read more here.

Read more

• Lubitsch in Berlin – box set review

• Sumurun: Pola Negri and Ernst Lubitsch’s Arabian night

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2015: Pordenone post No 1

The town was like a loaded gun, needing only a spark to set it off – Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

“It’s the last time I shall say it, so I shall say it,” began David Robinson, introducing what is surely not his final Giornate, but the last over which he will preside as artistic director. The Robinson era will close with the 34th Giornate del Cinema Muto, which looks on paper at least as if it will be a very special festival, with a jewel-studded programme. And he hands the baton to the surest of hands: the marvellous Jay Weissberg of Variety, who joined him on stage tonight by way of introduction, and performed as Robinson’s personal interpreter too. We said another goodbye on Saturday evening – this festival will be dedicated to the memory of one of its staunchest supporters, Jean Darling, who passed away in early September. A snippet of her singing Always at a previous festival began our gala evening, as Robinson took to the stage to say… what was it? Ah yes. “Welcome home!”

But before we get to the gala, and the speeches and the changing of the guard, we have a full afternoon of films to catch up on. Fasten your seatbelts, fellow Pordenauts*, we’re going on a journey.

Our world tour began with trip to Berlin – this was not classic Symphony of a City territory mind, but a visit to Gypsy Berlin – from the camp to the racetrack to the streets. Terrifying to think what lay in store for the people featured in this film, Grossstadt-Zigeuner (1932), but it was a true gem, directed by the Constructivist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy with great verve and edited with playful intricacy. Despite its many stylistic flourishes, it’s a warm, humane portrait, and served as an excellent introduction to the main feature in this afternoon’s bill from the Other City Symphonies strand. The longer film was a document of Chicago, made by a German film-maker Heinrich Hauser in 1931. Weltstadt in Flegeljahren. Ein Bericht uber Chicago (A World City in its Teens. A Report of Chicago) carried itself at an unexpectedly relaxed pace, puttering up the Mississippi on a paddle steamer for the longest time before reaching the metropolis, and even then, we moved slowly, until the film suddenly discovered the residents of the city. It was heartbreaking to see the poverty caused by the Great Depression, etched in the faces of men being turned away from labour exchanges. When workers unloading banana boats at the dock empty the rotten fruit into the river, another group of men in row boats appear to scoop them out of the water. Elsewhere in the city, too, on the south side in the streets largely populated by African Americans, on the lake beach bursting with sun worshippers, Chicago was defined by its people, not its towering skyscrapers. Hats off too to Philip Carli, for fantastic piano accompaniment for both films.

Next to Norway, for a flying visit, where we caught a luridly hand-painted tiger-taming short, in which the tamer’s hot pink shirt outshone the ferocious furries in the cage with him. And this morsel was to amuse our bouches for the first entry in the Russian Laughter strand, Nelzia li Bez Menia? (Vkusnoty) or Can’t You Just Leave Me out of This? (Delicious Meals) (1932). Opinion was divided on this one, but I thoroughly enjoyed it. This laugh-heavy Soviet propaganda comedy was, bizarrely, intended to promote the use of public canteens. Our hero is a discontented hubby, who hates cooking and tries out the canteen as an easy option. It’s completely disgusting, though he daren’t admit that to his wife. Thanks to some public-spirited activists and a newspaper campaign, however, the canteens are much improved – and when wifey fancies a change from her fella’s cooking they return to the scene of the food crime. It’s a weak joke in the finale: “Doesn’t hubby feel a fool that the food is so good, and the canteen so hygienic!” But the lead performance from Sergei Poliakov carries the show and the whole piece is a real delight. A delicious broth you might say, to tickle our tastebuds for the Italian beefcake to follow.

Forgive me for being crude, but how else to describe a strand called Italian muscle in Germany? Of the two famous strong men Carlo Aldini and Luciano Albertini it was Albertini’s turn to star today, in a confection called Mister Radio (1924). This German film was hugely watchable but skated perilously close to being utter tripe. What saved it from its ridiculous, threadbare plot and wooden acting were the imagination-defying stunts performed by our leading man. He leaped, he bounded, he dangled upside-down and carried four people at once on a single rope. The audience quite forgot itself and made an obscene amount of noise – gasping, laughing, gasping again. Impossible to resist doing so. It was exactly what, as John Sweeney pointed out afterwards, people who don’t watch silent films expect from a silent film. And although the plot was barely there, still Albertini ended up with the brunette with a past who really loved him, not the blonde ingenue with the terrible father, so … All’s well that ends well, as Shakespeare would say.

Which brings me to the gala evening. Two films tonight: one I simply adored and another that impressed rather than charmed me. Also, my eyelids were beginning to flutter. I had an early flight! And not enough coffee, certainly. First things first, Ernst Lubitsch and William Shakespeare seem to me a marriage made in heaven, and the director’s cheeky twist on Shakespeare’s tragedy of star-crossed lovers, Romeo und Julia im Schnee (1920) was a real tonic. This adaptation has only the scantest resemblance to the play and is in fact a mischievous rustic love story all of its own devising. I loved the fact that a legal dispute between the warring families came down to the weight of the sausages they sent to bribe the judge, and who could resist an apothecary who sells a young couple sugar water instead of poison and says they can pay the bill another time? All this, and Antonio Coppola’s deft original score, performed beautifully by a small orchestra.

The main feature of the evening, Maciste Alpino (1916) took us to the heart of the first world war, and the fighting in the Alps between the Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces. But this is an adventure comedy, not a real war flick, and while the scenery was monumental (a nod to the hand of Giovanni Pastrone), the tone was mostly light. Maciste is a handsome, heroic ogre, all superhuman strength and faultless patriotism, who could probably see off an entire army single-handedly. In one scene, he finds himself unarmed in a swordfight, so uses smoking firetongs instead. Why not? And he breaks his opponent’s sword, so … His almighty abilities did slacken the tension somewhat, I must admit. There were times also when I felt that the comedy was rather too gentle for the subject matter. But these are quibbles really – we saw a stunningly crisp restored print of a gorgeous film, with fantastic accompaniment from Philip Carli, Guenter Buchwald and Frank Bockius. Not the type of film one is likely to come across too often, and presented in the most immaculate way – that’s what we come to Pordenone for, after all.

Intertitle in-joke of the day

In the Chicago film, a shot of cattle ready for market was followed by the intertitle “The way of all flesh” – but that’s not on until next Saturday!

Hot topic of the day

Beyond the big news about Jay Weissberg taking over the reins next year, a delegate’s mind is liable to turn to material matters. The tote bag. Is it really, as it looks, made of paper? We hope not. Will it survive a rain shower? There is only one way to find out … the forecast for Sunday is not good.

Casual animal cruelty of the day

It has to be the little boy in the Russian film attempting to saw the tail off the family cat. Yikes.

- For more information on all of these films, the Giornate catalogue is available online here.

* Hat-tip to Nicky Smith for “Pordenauts”

Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2015: Pordenone post No 4

What is admirable in the clash of young minds is that no one can foresee the spark that sets off an explosion, or predict what kind of explosion it will be. – Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

Forgive me and my fellow delegates if we are a little dazed, but today an array of high-wattage stars dazzled the Verdi: Clara Bow, Ossi Oswalda and Douglas Fairbanks all took a turn in the spotlight, and didn’t we all know about it? But they were all playing second fiddle, I am afraid, to one of the festival’s guests of honour.

The real star of the day was Naum Kleiman, erstwhile director of the Moscow Cinema Museum, who was in town to deliver the Jonathan Dennis lecture at the Giornate. He didn’t really do that, though. He spoke a few words, and graciously answered our questions, but instead of a formal lecture we watched a new film that has been made about Kleiman, the Museum, and the frankly appalling state of affairs in Russia today, where the museum has been evicted and its good works all-but sacrificed to the opaque aims of the Ministry of Culture. It was called Cinema: a Public Affair, and it was directed by Tatiana Brandrup, who was also in attendance to answer questions. At an event where we have so much Russian cinema to celebrate, it is beyond distressing to learn that film culture in that country is in such a perilous position. Founded in 1989, the Cinema Museum used to show 20 – 20! – films a day. Important films, films from around the world, films that are now impossible to see in Russia. It was always run on a shoestring – Jean-Luc Godard made a gift to the Museum of a Dolby sound system ahead of a retrospective of his works there. But now, the situation is as absurd as something in one of the Soviet comedies screening at the Giornate. A new building intended to house the Museum has been repurposed as a parking garage, while the Museum’s collections are all in temporary storage at yes, garages at the Mosfilm studios…

Kleiman is an inspiring man, who spoke in the film movingly about the first film he remembered seeing as a four-year-old child. Before that point he had seen war, he had seen fear and devastation, in fact his own father was missing, but one night at a park near his refugee camp in Tashkent, he saw the cinema for the first time. That screening of Michael Powell’s The Thief of Bagdad was to him a “window on to another reality”. He stood on his bench, and flapped his hands, imagining that he had a magic carpet under his feet. And he has dedicated his life to sharing that magic, that escape, that understanding of a different world, with other people. A member of the Verdi audience asked simply: “How do you find the strength to go on fighting?” “I’m not fighting,” he replied. “I’m just working.”

For Kleiman, the conversation that films can spark are almost the point of screening them. “The film begins when it’s over,” he said. And although they were lighthearted in tone, this morning’s programme of shorts illustrated that perfectly. A package put together by Laura Horak on the theme of cross-dressing girls on film, these movies, which were mostly comedies, were hugely intriguing, and provided delicious food for thought. The shorts included actresses playing boys, playing dual roles or simply playing characters who dress up as lads, or take on male characteristics. The way that the teens and twenties of the last century approach these ideas is consistently intriguing – so often they skirt close to something really subversive, something to challenge the relentless heterosexuality of so much silent Hollywood cinema, and then retreat, having nibbled their doughnut and kept it too. I enjoyed Anna Q Nilsson as a rebel spy in disguise during the civil war in The Darling of the CSA (1912) (riding sidesaddle even when in drag). I also liked a futuristic “nightmare” of 21st-century gender role reversals called What is the World Coming to? (1926), a surprisingly nifty restoration of a 16mm print, in which a kept husband worries that his bigshot wife spends too much time with her “sheik stenographer”.

More women bursting the bounds in two of today’s most popular screenings. First, Ossi Oswalda played a woman, and a doll, of healthy appetites and heartening fearlessness in Ernst Lubitsch’s freaky fairytale Die Puppe (1919). From the unpacking of the set to the happy finale, this film offers unalloyed glee: a sexy, satirical Coppelia. I can’t get enough of it. As the automaton said to the Baron’s nephew …

And while we’re on the subject of automata, a modern silent from Iran, Junk Girl (2015), may have taken a few of us by surprise this afternoon. This touching stop-motion animation took us inside the world of a young woman thrown on the scrapheap, metaphorically, physically and figuratively. A little strange and very poignant.

Then this evening, Clara Bow took to the stage and earned a round of applause all of her own. A message to the lovelorn ladies and gentlemen in the auditorium – it’s just a moving picture, I’m afraid. Discussion over drinks later touched on the subject of Clara’s charms: mannered or just marvellous? Well Clara herself would tell you it’s all an act baby, lips and eyes and hips and thighs. She’s playing an unstoppable flirt in this one, Mantrap (1926), which is just as well, and the fact that you can’t tell whether she means it or not is just the risk you take in this life I guess. But Clara is always tops in my book, and here directed by Victor Fleming, photographed by James Wong Howe and seducing the divine Ernest Torrence … well, who could ask for anything more? Sublime accompaniment by Philip Carli? Well yes, we had that too. Mantrap is a first-rate romcom, and I would love to know if say, Amy Schumer or Kristen Wiig puts this movie at the top of their best-of-all-time-ever lists.

Clara was preceded by a strong programme of shorts. I enjoyed a charming, bitesized Max Linder comedy, Petite Rosse (1909), directed by Camille de Morlhon, in which he learns to juggle, or rather doesn’t, in order to win a fair lady’s hand. And Wake Up Lenochka (1934) was as sweet and bright as a lemon drop – this Soviet comedy short was a simple skit on a girl who stays up late reading and can’t get out of bed and to school on time. Directed with charm and flair by Antonina Kudriavtseva with a winning performance from 25-year-old Yaninia Zheimo as the dozy schoolgirl. Despite appearances, only the second of those was actually directed by a woman – which to be fair is a pretty good ratio here.

I am leaving Douglas Fairbanks until last, in the hope that you won’t read this far and so won’t sigh and say “not him again!”. Sorry, but The Mark of Zorro (1920) is like a chocolate-sprinkled double cappuccino on a cloudy morning: luxuriant, sweet and with enough kick to motor your whole day. And the only man I know with enough zest and brio to match Dougie was in the theatre and on the piano – we were treated to a superb Spanish-flavoured accompaniment from Neil Brand, with Frank Bockius upping the tempo on percussion. In this landmark California swashbuckler, Fairbanks is both the slinky Robin Hood in black satin who carves the faces of evil men with his gleaming blade, and his dorky alter ego Don Diego. He’s irresistible in one role, with a flashing smile and spring-loaded legs, and adorable in the other. Fairbanks is a class act, even if you do think he is a terrible showoff, because he makes all this show business look like it’s a breeze. Don’t fight it, feel it.

Intertitle of the day

“Oh, the obscenity!” A chorus of high-kicking dolls scandalises young Lancelot in Die Puppe.

Dish of the day

No sausages for your dinner guests? No problem. In a dream sequence during the Keystone short Dollars and Sense (1916), an alternative presents itself. Take one beloved pet puppy, dunk it in the parlour player-piano and play a little tune. Hey presto, a string of bow-wow bangers will emerge, wearing a ribbon and wagging its little doggy tail. Ugh!

Euphemism of the day

Have you been “worrying about Woodbury”, like the folks in Mantrap? Chance would be a fine thing, I dare say …

Insult of the day

“You idlers! You wasters! You fashion-plates!” Doug corrals the tipsy caballeros in The Mark of Zorro.

- For more information on all of these films, the Giornate catalogue is available online here